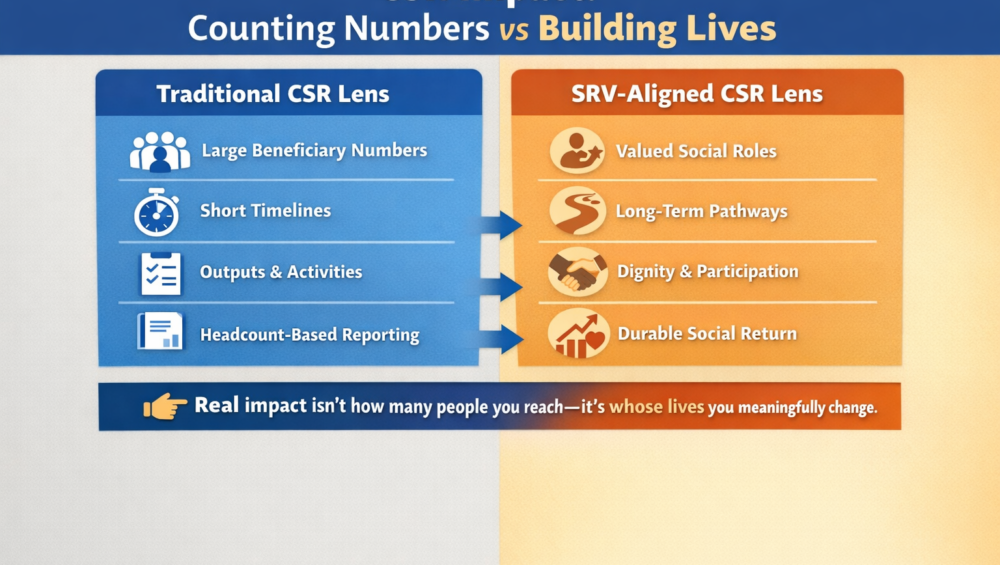

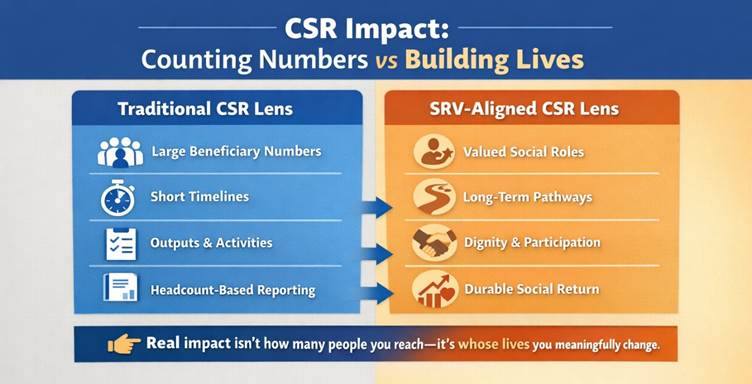

Every year, Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) investments in India channel significant resources into education, therapy, skill development, and employment initiatives for persons with disabilities. These efforts are well-intentioned and often substantial in scale. Yet a critical question continues to sit at the margins of CSR decision-making:

Are these investments enabling people to live meaningful, valued lives in society — or are they primarily sustaining services and short-term outputs?

Social impact leaders, disability scholars, and CSR practitioners increasingly agree that services alone do not guarantee inclusion. Decades of disability research demonstrate that what ultimately determines life outcomes is not the volume of services delivered, but the social roles people are enabled to hold in their families, workplaces, and communities (Wolfensberger, 1983; Thomas & Wolfensberger, 1999).

Social Role Valorization (SRV) offers CSR leaders a powerful framework to move beyond counting activities and beneficiaries toward enabling dignity, contribution, and long-term social integration. In India’s evolving CSR ecosystem — marked by heightened compliance, transparency, and accountability — this shift is not only ethical, but strategically sound.

Why inclusion alone is not enough

Disability experts have long cautioned against equating inclusion with access to services. SRV explains why: people who occupy valued social roles — such as learner, worker, neighbour, volunteer, artist, or contributor — gain greater access to respect, relationships, opportunities, and material resources. Conversely, individuals confined to devalued roles — such as “dependent,” “burden,” or “permanent beneficiary” — continue to face exclusion, regardless of how many services they receive.

For CSR leaders, this distinction is not theoretical. Global research consistently links valued social roles with durable outcomes:

- Greater independence and self-worth

- Reduced long-term dependency on families and institutions

- Stronger community participation and social capital

- More meaningful and sustained social return on investment

From a social impact perspective, SRV reframes CSR from funding activities to building futures. This aligns closely with the intent of Indian CSR law, which positions CSR as a contributor to sustainable development outcomes under Schedule VII of the Companies Act, rather than as episodic philanthropy.

The Conservatism Corollary: why neurodiversity work costs more — and must

Within SRV theory, the Conservatism Corollary articulates a reality often overlooked in CSR budgeting and reporting:

People who have been deeply devalued require stronger, richer, and more sustained supports to overcome the cumulative effects of exclusion.

For neurodivergent individuals — particularly those with autism and developmental disabilities — years of stigma, segregation, and low expectations create layered disadvantages. Disability researchers and practitioners emphasise that quality, intentionality, and continuity of support matter far more than speed or scale.

This helps explain why per-beneficiary costs in neurodiversity-focused programmes are often higher. From an SRV lens, this is not inefficiency; it is the necessary work of restoring dignity and rebuilding opportunity after prolonged devaluation. Doing “just enough” for deeply marginalised populations is not neutral — it actively perpetuates inequality.

In today’s CSR compliance environment — with greater emphasis on due diligence, professional certification of implementing agencies, and transparent impact logic (including CSR-1 registration requirements) — investments that prioritise depth, rigour, and defensible outcomes are increasingly credible and resilient.

The uncomfortable truth: neurodiversity impact will not come in mass numbers

Mainstream CSR reporting mechanisms often privilege:

- Large beneficiary counts

- Rapid milestones

- Standardised, easily quantifiable outputs

However, research in neurodevelopment and disability consistently shows that progress for neurodivergent individuals is slow, non-linear, and highly individualised (Shattuck et al., 2012; Roux et al., 2015). Gains often appear in subtle but transformative ways — communication, emotional regulation, self-advocacy, confidence, and agency.

From both an SRV and human development perspective:

- Impact cannot be rushed or mass-produced

- Slow progress does not equal low impact

- Deep individual change for highly devalued groups is among the most durable forms of social impact

Such progress expands real capabilities (Sen, 1999; Nussbaum, 2011), not just reported outputs — a distinction increasingly recognised by serious social impact investors.

Skills without social value fall short

Many CSR programmes evaluate success through metrics such as:

- Therapy hours delivered

- Skills taught

- Certifications completed

While these indicators are important, disability scholars caution that skills alone do not guarantee inclusion if they are not translated into socially recognised roles. Without pathways into real-world participation, individuals often remain:

- Segregated from mainstream society

- Dependent on families or institutions

- Invisible in economic and civic life

SRV insists that learning and skill development must culminate in real contribution — roles that are visible, valued, and acknowledged by the wider community. This principle resonates strongly with Schedule VII’s emphasis on sustainable societal outcomes rather than short-term service delivery.

Employment: why neurodivergent inclusion takes time — and courage

Employment remains one of the most challenging inclusion frontiers for neurodivergent individuals in India and globally. Research identifies persistent barriers in recruitment practices, workplace culture, job design, and support systems (Scott et al., 2019; Bury et al., 2023).

Evidence-based approaches such as customised employment, aligned with SRV, demonstrate what effective inclusion requires:

- Job roles redesigned around individual strengths

- Sensitised supervisors and co-workers

- Flexible productivity and performance expectations

- Ongoing mentoring and coaching

- Time for adjustment, trust-building, and stability

Systematic reviews confirm that these supports — while resource-intensive — are essential for retention, dignity, and long-term participation (Doyle & McDowall, 2024). For companies, this work demands patience and courage. But it is precisely here that authentic inclusion takes root.

What SRV-aligned CSR investment looks like in practice

At Ashish Foundation, SRV principles guide programme design across education, therapy, vocational training, and employment pathways. SRV-aligned CSR partnerships are characterised by:

- High expectations and dignity-centred learning environments

- Individualised supports responsive to life context

- Skill development linked to real contribution

- Community participation rather than segregation

- Long-term engagement with families, employers, and local ecosystems

The outcome is not merely “trained beneficiaries,” but individuals increasingly recognised as learners, workers, creators, colleagues, and citizens.

SRV and Indian CSR compliance: a strong alignment

Recent CSR compliance reforms in India — including mandatory CSR-1 registration, enhanced disclosures, and closer scrutiny of implementing agencies — signal a shift toward greater accountability and quality in CSR partnerships.

These reforms align naturally with SRV-informed approaches:

- Clear justification for higher per-beneficiary investments

- Evidence-based rationale for long-term funding cycles

- Defensible logic for smaller cohorts with deeper outcomes

- Impact narratives grounded in dignity, participation, and role stability

Organisations with demonstrated expertise in neurodiversity and SRV-aligned practice are therefore well positioned within this regulatory landscape.

Rethinking scale, timelines, and impact reporting

In SRV-aligned CSR:

- Scale may mean replicable models, not large numbers

- Success may mean role stability and retention

- Impact may unfold over years, not quarters

Meaningful indicators include:

- Progression into valued social roles

- Reduced long-term dependency

- Workplace retention and engagement

- Improved quality of life, agency, and social participation

These outcomes are durable, human-centred, and consistent with both CSR policy intent and Schedule VII objectives.

From charity to contribution

The most effective CSR does not ask:

How many people did we support?

It asks:

Whose lives did we meaningfully enable?

By investing in SRV-aligned neurodiversity initiatives, CSR leaders choose intentional, patient, and transformative inclusion. Such investments may not generate mass numbers — but they deliver dignity, contribution, and futures that endure.

As CSR leaders and social impact practitioners, are we prepared to invest not only in programmes — but in the time, intensity, and quality required to undo years of devaluation and enable truly valued lives?

—-

References & Sources

- Ministry of Corporate Affairs (MCA), Government of India. Companies Act, 2013 and Companies (Corporate Social Responsibility Policy) Rules, 2014, including subsequent amendments.

- Ministry of Corporate Affairs (MCA), Government of India. CSR-1 Form: Registration of Entities for Undertaking CSR Activities.

- India Briefing. Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) in India: Legal Framework and Compliance Requirements.

- TaxGuru. Recent Amendments and Enforcement Trends in CSR Compliance under the Companies Act, 2013.

- Wolfensberger, W. (1983). Social Role Valorization: A Proposed New Term for the Principle of Normalization. Syracuse University.

- Wolfensberger, W., & Thomas, S. (1999). A Brief Introduction to Social Role Valorization. Syracuse University.

- Thomas, S., & Wolfensberger, W. (2005). An Overview of Social Role Valorization Theory. SRV Press.

- Sen, A. (1999). Development as Freedom. Oxford University Press.

- Nussbaum, M. (2011). Creating Capabilities: The Human Development Approach. Harvard University Press.

- Shattuck, P. T., et al. (2012). Post-High School Service Use Among Young Adults with Autism Spectrum Disorder. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders.

- Roux, A. M., et al. (2015). National Autism Indicators Report: Transition into Young Adulthood. Drexel University.

- Scott, M., Falkmer, M., Girdler, S., & Falkmer, T. (2019). Factors Contributing to Successful Employment for Adults with Autism Spectrum Disorder. PLOS ONE.

- Bury, S. M., et al. (2023). Barriers and Facilitators to Employment for Neurodivergent Individuals: A Systematic Review. Autism Research.

- Doyle, N., & McDowall, A. (2024). Neurodiversity at Work: Evidence-Based Pathways to Inclusion. CIPD.