Rethinking Disability, Dignity, and Human Flourishing through SRV and Amartya Sen’s Capability Approach

What does it mean to live a good life?

For decades, development, education, and disability systems have tried to answer this question through metrics of productivity, independence, economic output, or charity-based support. However, a growing body of scholarship has shown that such measures often fail to capture what truly matters for human well-being: whether people can live lives they have reason to value (Sen, 1999).

Two influential frameworks—Amartya Sen’s Capability Approach and Social Role Valorization (SRV)—offer a deeper, more humane understanding of human flourishing. When brought together, they reveal a compelling truth:

An abundant, meaningful, and dignified life is not a favour—it is a fundamental human right for every person, including persons with disabilities (PWDs) and neurodivergent individuals.

At Ashish Foundation for the Differently Abled Charitable Trust (AFDA), this intersection is not theoretical. It is lived—every day, in classrooms, homes, communities, and workplaces.

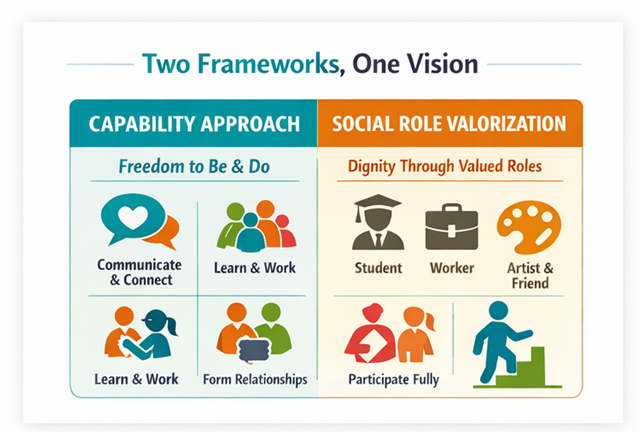

The Capability Approach: Freedom to Be and Do

Amartya Sen reframed development by shifting attention away from income, IQ, or productivity toward capabilities—the real freedoms people have to be and do what they value (Sen, 1999; Sen, 2009).

Within this framework, functionings refer to the actual beings and doings of a person—what individuals can achieve in real life, such as communicating, participating, working, or forming relationships. While capabilities represent the range of possible lives a person can choose from, functionings reflect the realized outcomes of those choices (Sen, 1992).

Capabilities include:

- The ability to communicate and express oneself

- The freedom to participate in social and community life

- The opportunity to form relationships and friendships

- The chance to learn, work, create, and contribute

Sen emphasized that inequality arises not merely from lack of resources, but from failures of conversion—when social structures, attitudes, environments, and policies prevent individuals from converting available resources and supports into meaningful functionings (Sen, 1992; Nussbaum, 2011).

For persons with disabilities, this distinction is critical: possessing a service, aid, or intervention does not automatically lead to a good life unless it translates into real participation, valued roles, and lived experiences.

Disability is not simply an individual impairment; it is a capability deprivation shaped by social, institutional, and attitudinal barriers. This perspective aligns strongly with the UN Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (UNCRPD), which frames disability inclusion as a matter of rights, participation, and freedom rather than welfare.

Social Role Valorization: Why Roles Shape Dignity

Social Role Valorization (SRV), developed by Dr. Wolf Wolfensberger, complements the Capability Approach by explaining how social perception determines access to those freedoms (Wolfensberger, 2013).

SRV asserts that:

The roles people occupy in society largely determine how they are treated, valued, and included.

People in valued social roles—such as student, worker, artist, friend, neighbour, or citizen—are more likely to experience respect, opportunity, and belonging.

Those cast into devalued roles—patient, burden, charity case, eternal child, or object of pity—are more likely to face exclusion, low expectations, segregation, and dependency.

Research on disability representation consistently shows that negative or infantilizing roles lead to internalized stigma, reduced self-determination, and limited life outcomes (Shakespeare, 2014; Goodley, 2016).

Even well-meaning labels—“inspirational,” “divyangjan,” “special”—can unintentionally distance or pedestalize people with disabilities, rather than normalize equality. As SRV reminds us, pity and heroism are two sides of the same exclusionary coin.

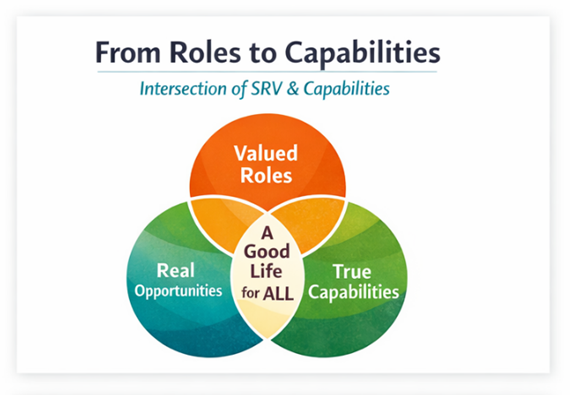

Where SRV and Capabilities Meet: A Conceptual Intersection

The intersection of SRV and the Capability Approach is conceptually powerful and practically urgent:

- Capabilities require opportunities

- Opportunities depend on social roles

- Roles determine whether freedoms are real or merely theoretical

In other words:

Capabilities cannot be built in isolation. They flourish when individuals are seen, supported, and expected to participate as valued members of society.

This insight is increasingly reflected in disability studies literature, which emphasizes participation, relational autonomy, and social inclusion over purely clinical or individual models of support (Mitra, 2006; Goodley, 2016).

This intersection forms the foundation of the AFDA model.

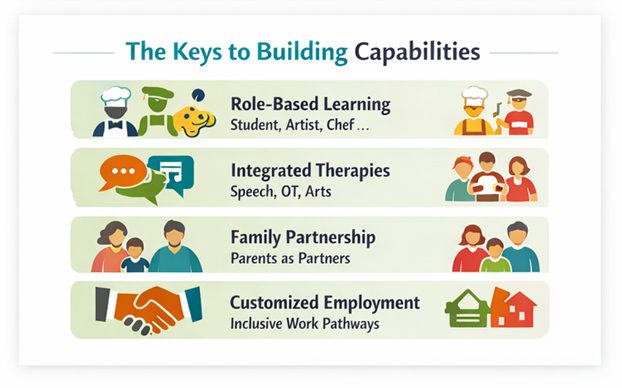

The AFDA Model: Building Capabilities by Building Roles

At Ashish Foundation, learning goes far beyond classrooms or therapy rooms. The central question guiding practice is simple yet radical:

“What valued role is this child or young adult growing into?”

1. A Capability Pathway, not a Deficit Program

Each learner’s journey is unique. AFDA focuses on enabling core human capabilities:

- Communicating with purpose – through speech, alternative communication, expression, and social understanding

- Participating meaningfully – in home routines, classrooms, markets, libraries, metro travel, and community spaces

- Building age-appropriate roles for adulthood – as learners, helpers, creators, artists, teammates, and workers

Cooking is not just life-skills training—it is stepping into the role of a chef.

Art is not therapy—it is becoming an artist.

Travel is not exposure—it is learning to be a confident commuter and citizen.

This learning-by-doing approach aligns with research on experiential and community-based learning, which shows improved functional outcomes, emotional regulation, and long-term independence for neurodivergent learners (Kolb, 1984; Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 2021).

2. Therapies that Integrate, Not Isolate

AFDA deliberately rejects siloed, clinic-only models.

Speech therapy, occupational therapy, sensory integration, art, music, and behavioural support are woven into daily routines and real-life contexts—because capabilities only matter if they translate into lived experience.

This reflects both:

- SRV: real roles in real places

- Capability theory: functionings over abstract skills

Integrated therapeutic models are increasingly recognized as best practice for inclusive education and developmental support (WHO, 2011; UNESCO, 2019).

3. Interdependence Over False Independence

Both SRV and the Capability Approach challenge the myth of absolute independence.

Human flourishing is inherently interdependent.

Friendship, collaboration, shared support, and mutual contribution are not signs of weakness; they are hallmarks of a good life. Contemporary disability scholarship emphasizes relational autonomy, where dignity is preserved through choice, support, and belonging rather than isolation (Kittay, 2011).

AFDA actively nurtures friendships, peer relationships, and community participation, recognizing that belonging itself is a core human capability.

4. Families as Capability Partners

Capabilities do not develop in isolation.

AFDA works closely with families through:

- Regular parent training and counselling

- Collaborative goal-setting

- Guidance for transitions, adolescence, and independent or supported living

Family-centred and collaborative models have been shown to significantly improve long-term participation and well-being outcomes for children with developmental disabilities (Dunst et al., 2007).

5. Customized Employment as Role Realization

Employment at AFDA is not about forcing uniform outcomes.

It is about role matching:

- Identifying strengths, interests, sensory needs, and pace

- Designing customized vocational pathways

- Connecting learners with inclusive workplaces and community-based projects

Here, work is not just income—it is identity, dignity, and contribution, echoing both Sen’s emphasis on meaningful functionings and SRV’s focus on socially valued roles

Why This Matters: From Charity to Justice

When people with disabilities are denied valued roles, they are denied capabilities.

When they are denied capabilities, they are denied the good life.

This is not unfortunate—it is unjust.

As Amartya Sen reminds us, justice is about expanding substantive freedoms.

As SRV reminds us, freedoms are socially constructed through roles.

Together, they compel us to rethink disability inclusion—not as welfare, but as a matter of rights, dignity, and human flourishing.

A Call to Action

If we truly believe that every human being has the right to a good quality of life, we must ask:

- What roles are our schools, workplaces, and policies creating?

- Whose capabilities are being expanded—and whose are being constrained?

- Are we building systems that prepare people for life, or merely managing difference?

At Ashish Foundation, the answer is clear:

We build roles for life—because when people have roles, they discover capabilities. And when they discover capabilities, they claim their rightful place in the world.

—

References & Literature

- Sen, A. (1992). Inequality Reexamined. Oxford University Press.

- Sen, A. (1999). Development as Freedom. Oxford University Press.

- Sen, A. (2009). The Idea of Justice. Harvard University Press.

- Nussbaum, M. (2011). Creating Capabilities: The Human Development Approach. Harvard University Press.

- Wolfensberger, W. (2013). Social Role Valorization: A Proposed New Term for the Principle of Normalization. Keystone Institute.

- Mitra, S. (2006). “The Capability Approach and Disability.” Journal of Disability Policy Studies.

- Goodley, D. (2016). Disability Studies: An Interdisciplinary Introduction. Sage.

- Shakespeare, T. (2014). Disability Rights and Wrongs Revisited. Routledge.

- Kittay, E. F. (2011). “The Ethics of Care, Dependence, and Disability.” Ratio Juris.

- UNESCO (2019). Disability and Education in India.

- World Health Organization (2011). World Report on Disability.

- Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders (2021). Community participation and functional independence outcomes.

- Silberman, S. (2015). NeuroTribes: The Legacy of Autism and the Future of Neurodiversity. Penguin.

- Keystone Institute India (2022). SRV and Inclusive Education Practices in India.