Based on training inputs by Mrs. Viveka Chattopadhyay

| Summary: At Ashish Foundation, learning is designed as an experience—rooted in exploration, participation, and real life—rather than a set of instructions. Through the Discovery Method, or learning by doing, children with autism and developmental disabilities engage with concepts through hands-on, multi-sensory, and visually structured learning, moving beyond rote teaching toward meaningful understanding. Grounded in Jerome Bruner’s constructivist theory, this approach supports learning that progresses from concrete action to visual organisation and, finally, to conceptual and symbolic understanding. Practices such as Treasure Baskets, holistic language development, mind mapping across subjects, play-based numeracy, and experiential learning in Science and EVS allow learners to explore ideas, make connections, and construct meaning at their own pace, with thoughtful guidance. Discovery-based and mind-mapped learning nurtures curiosity, agency, and functional understanding while reducing fear of failure and over-dependence on prompts. Integrated with Social Role Valorisation (SRV), it positions learners as active participants, problem-solvers, and contributors within their learning environments. Aligned with the Capability Approach, the focus shifts from narrow academic outcomes to expanding what learners are able to do and be—supporting autonomy, choice, and meaningful participation in everyday life. At Ashish Foundation, learning is not about providing answers; it is about creating environments where children can discover, develop competence, and build lives that are valued, inclusive, and rich with possibility. |

When Learning Becomes an Experience

Discovery, Mind Mapping, and Learning by Doing at Ashish Foundation

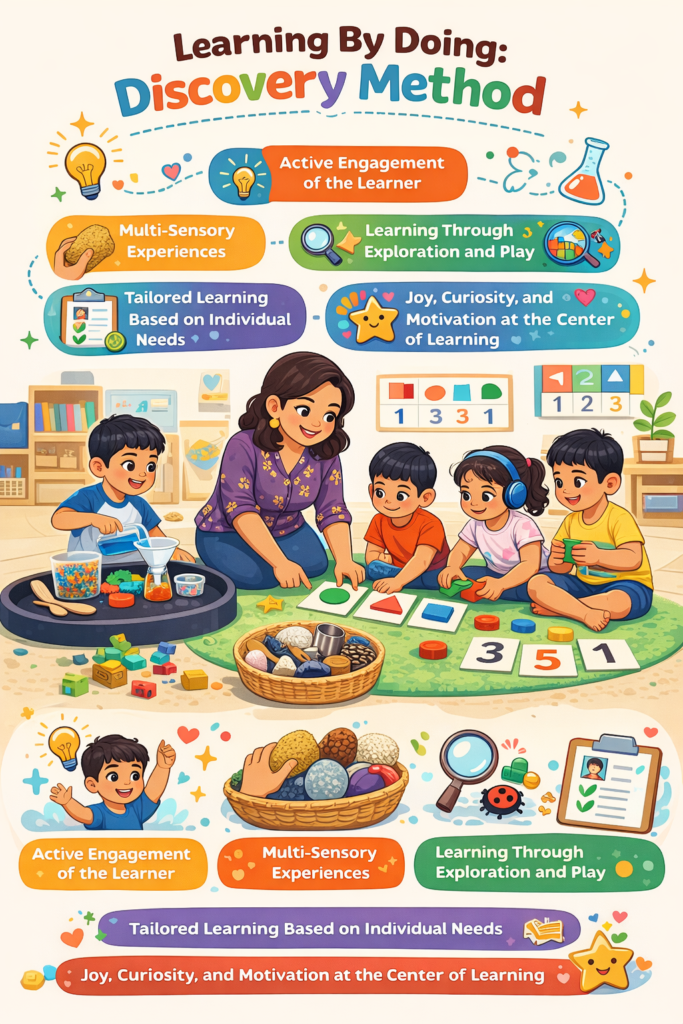

At Ashish Foundation, we begin with a simple but powerful belief: every child can learn—when learning is meaningful, respectful, and connected to real life. For children with autism and developmental disabilities, learning is most effective when it is not imposed, but experienced.

Across our classrooms and therapy-integrated learning spaces, one approach consistently brings this belief to life—the Discovery Method, often described as learning by doing. This approach allows children to engage actively with the world through touch, movement, exploration, visual organisation, and choice, rather than through rote instruction or passive worksheets.

Learning, in this sense, becomes something children do, experience, and make meaning from—not something done to them.

Discovery Learning: Theory Grounded in Practice

The Discovery Method was articulated by psychologist Jerome Bruner (1961), a key figure in constructivist learning theory. Bruner proposed that learning is most effective when learners actively construct knowledge through experience rather than passively receive information.

He described three interconnected modes of learning:

- Enactive – learning through doing and physical manipulation

- Iconic – learning through images, visuals, and spatial organisation

- Symbolic – learning through language, numbers, and abstract symbols

This progression—from action to abstraction—is especially relevant for children with autism and developmental disabilities. Research shows that experiential, discovery-based learning supports deeper conceptual understanding, intrinsic motivation, and better long-term retention, particularly when learning is thoughtfully guided rather than minimally structured (Alfieri et al., 2011; Kirschner et al., 2006).

At Ashish Foundation, this progression is intentionally supported through hands-on exploration, visual scaffolds such as mind maps, and structured opportunities to connect experience with language and symbols.

Multi-Sensory and Visual Learning for Autistic Learners

Decades of research in autism and developmental science highlight the importance of multi-sensory and visually structured learning environments. Many autistic learners process information more effectively when learning includes tactile, visual, proprioceptive, and movement-based experiences (Ayres, 1972; Dunn, 2007).

At Ashish Foundation, learning often begins with objects, actions, and visual organisation. Children are encouraged to:

- Touch and feel

- Manipulate materials

- Observe cause and effect

- Explore through repetition and variation

These sensory-rich and visually supported experiences help children build meaning before language, reduce anxiety, support regulation, and strengthen attention. From a Universal Design for Learning (UDL) perspective, this approach provides multiple means of representation and engagement, ensuring access for learners with diverse processing profiles (Meyer, Rose & Gordon, 2014).

From a Social Role Valorisation (SRV) perspective, this positions children as active learners rather than passive recipients of care—supporting valued roles such as learner, explorer, and participant.

Mind Mapping as a Core Pedagogical Tool Across Subjects

At Ashish Foundation, mind mapping is a central pedagogical strategy used across all subjects, including Language, Mathematics, Environmental Studies (EVS), and Science.

Mind maps allow children to organise information visually and non-linearly, helping them see relationships between ideas rather than memorising isolated facts. Research on mind mapping and concept mapping shows that visual organisation of knowledge:

- Supports comprehension and recall

- Reduces cognitive load

- Strengthens conceptual connections

- Aligns strongly with constructivist learning principles (Buzan, 2006; Novak & Cañas, 2008; Davies, 2011)

Mind mapping also supports Bruner’s iconic-to-symbolic transition, acting as a bridge between experience and abstract representation.

Teaching Language Through a Holistic, Multi-Sensory Mind Mapping Approach

Language learning at Ashish Foundation is approached holistically, recognising that words gain meaning only when they are connected to experience, understanding, and use.

Rather than teaching vocabulary in isolation, we first build mind maps around an object, concept, or theme. Using a multi-sensory framework, children explore:

- The name of the object

- What you can do with it (function and action)

- What it is made of

- Its features (size, colour, shape, parts)

- Its category and relationship to other objects

This approach allows language to develop alongside cognition, sensory processing, and functional understanding. Children move from experience to expression—strengthening comprehension, communication, and generalisation (Beck et al., 2013; Paul, 2007).

From a Capability Approach perspective, this method expands children’s real opportunities to communicate meaningfully in daily life—not just to label, but to describe, explain, question, and participate (Sen, 1999; Nussbaum, 2011).

Mind Mapping in Mathematics, EVS, and Science

The same discovery-based and mind-mapping principles guide academic learning across subjects.

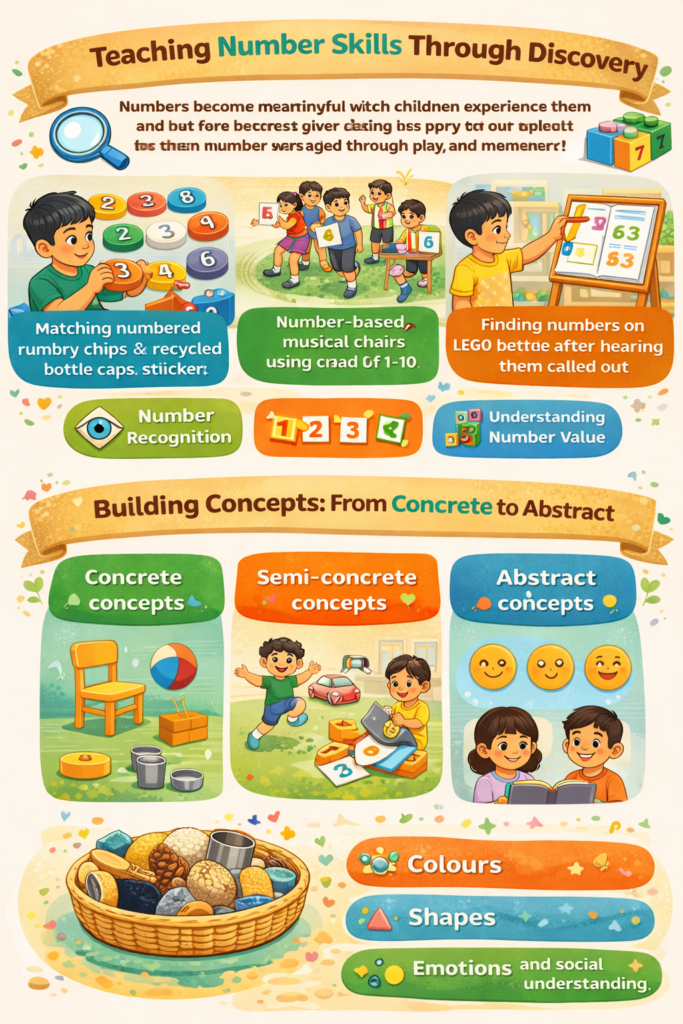

Mathematics

In Mathematics, mind maps are used to visually represent:

- Number concepts and relationships

- Operations such as grouping, addition, and subtraction

- Sequencing, patterns, and order

- Real-life applications of numbers

This helps children understand how numbers work together, moving beyond rote counting to conceptual understanding.

EVS and Science

In Environmental Studies (EVS) and Science, concepts are first introduced through multi-modal theory sessions—using visuals, mind maps, objects, stories, demonstrations, and discussion.

This is followed by hands-on application, where students:

- Conduct simple experiments

- Build models

- Observe changes and outcomes

- Connect concepts to everyday life

Mind maps help students organise information about plants, animals, materials, weather, and environmental processes, making abstract concepts accessible and meaningful.

This mirrors how neurotypical peers encounter learning in mainstream settings and reflects our belief that students with disabilities deserve access to the same breadth, depth, and richness of learning—adapted thoughtfully, not reduced.

The Treasure Basket: Discovery Through Everyday Objects

One simple yet powerful discovery-based tool we use is the Treasure Basket, inspired by early childhood pedagogy and sensory integration research.

A Treasure Basket is a low-sided basket filled with everyday, real-world objects such as:

- Wooden items

- Metal objects

- Fabric pieces

- Household materials with varied textures, weights, and sounds

Children are invited to explore freely—using their hands, fingers, feet, and sometimes their mouths (with careful supervision).

Through this exploration, children begin to discover:

- Weight, size, and balance

- Texture, shape, and temperature

- Sound and cause-effect relationships

- Sensory preferences and differences

Research on play-based and exploratory learning shows that such open-ended experiences promote curiosity, problem-solving, and generalisation of skills to real-life contexts (Vygotsky, 1978; Lifter et al., 2011).

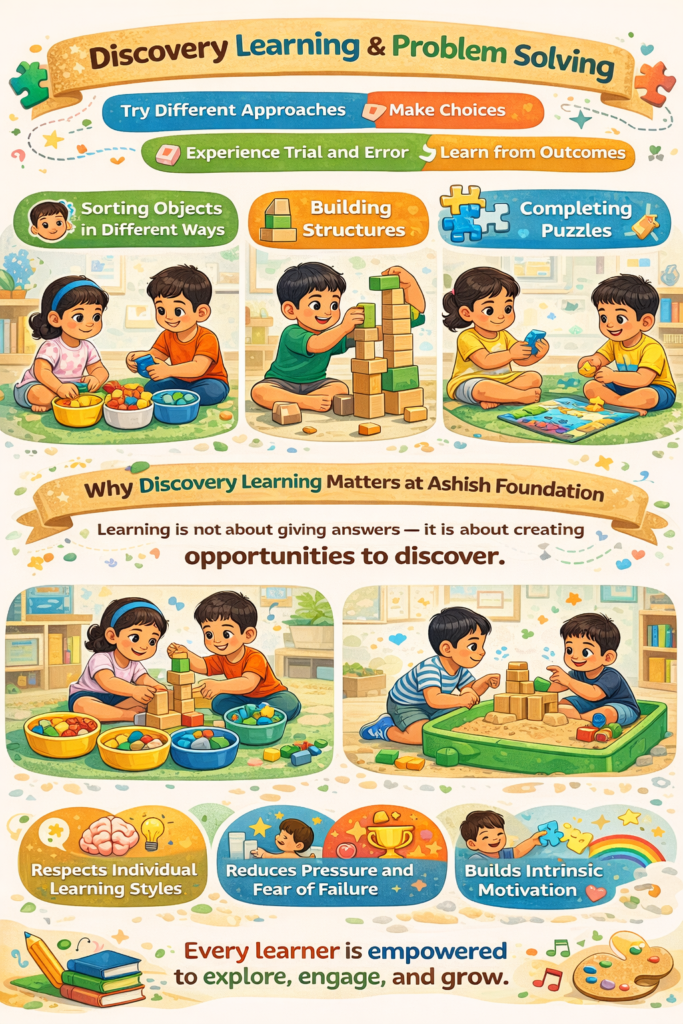

Discovery Learning and Problem-Solving

Discovery-based learning plays a vital role in developing problem-solving and flexible thinking. Children are encouraged to:

- Try different strategies

- Make choices and decisions

- Experience trial and error safely

- Reflect on outcomes

Activities may include sorting, building, puzzles, and navigating challenges during play. From an SRV perspective (Wolfensberger, 1983), these opportunities support valued roles such as decision-maker, problem-solver, and competent participant—countering deficit-based narratives.

Why Discovery Learning Matters at Ashish Foundation

For children with autism and developmental disabilities, discovery-based, visually structured, and mind-mapped learning:

- Respects individual learning styles

- Reduces pressure and fear of failure

- Builds intrinsic motivation and competence

- Strengthens academic, functional, and life skills

- Makes learning joyful, meaningful, and relevant

At Ashish Foundation, learning is not about providing answers—it is about creating environments where discovery, dignity, and participation are possible.

By integrating Discovery Learning, Mind Mapping, Social Role Valorisation, and the Capability Approach, our practice moves beyond skill acquisition toward autonomy, inclusion, and meaningful lives.

Education, in this sense, is not preparation for life—it is life itself.

—

References

Alfieri, L., Brooks, P. J., Aldrich, N. J., & Tenenbaum, H. R. (2011). Does discovery-based instruction enhance learning? Journal of Educational Psychology, 103(1), 1–18.

Ayres, A. J. (1972). Sensory Integration and Learning Disorders. Los Angeles: Western Psychological Services.

Beck, I. L., McKeown, M. G., & Kucan, L. (2013). Bringing Words to Life: Robust Vocabulary Instruction. New York: Guilford Press.

Bruner, J. S. (1961). The act of discovery. Harvard Educational Review, 31(1), 21–32.

Browder, D. M., Spooner, F., & Bingham, M. A. (2009). Teaching language arts to students with severe developmental disabilities. Research and Practice for Persons with Severe Disabilities, 34(1–2), 39–53.

Buzan, T. (2006). The Mind Map Book. London: BBC Active.

Davies, M. (2011). Concept mapping, mind mapping and argument mapping: What are the differences and do they matter? Higher Education, 62(3), 279–301.

Dunn, W. (2007). Supporting children to participate successfully in everyday life by using sensory processing knowledge. Infants & Young Children, 20(2), 84–101.

Kirschner, P. A., Sweller, J., & Clark, R. E. (2006). Why minimal guidance during instruction does not work. Educational Psychologist, 41(2), 75–86.

Kolb, D. A. (1984). Experiential Learning: Experience as the Source of Learning and Development. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall.

Lifter, K., Mason, E. J., & Barton, E. E. (2011). Children’s play: Where we have been and where we could go. Journal of Early Intervention, 33(4), 281–297.

Meyer, A., Rose, D. H., & Gordon, D. (2014). Universal Design for Learning: Theory and Practice. Wakefield, MA: CAST.

Novak, J. D., & Cañas, A. J. (2008). The theory underlying concept maps and how to construct and use them. IHMC CmapTools Technical Report.

Nussbaum, M. C. (2011). Creating Capabilities: The Human Development Approach. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Odom, S. L., Thompson, J. L., Hedges, S., et al. (2015). Technology-aided interventions and instruction for individuals with autism spectrum disorder. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 45(12), 3805–3819.

Paul, R. (2007). Language Disorders from Infancy Through Adolescence. St. Louis, MO: Mosby.

Schreibman, L., Dawson, G., Stahmer, A. C., et al. (2015). Naturalistic developmental behavioral interventions. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 45(8), 2411–2428.

Sen, A. (1999). Development as Freedom. New Delhi: Oxford University Press.

United Nations. (2006). Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities. New York: United Nations.

UNESCO. (2017). A Guide for Ensuring Inclusion and Equity in Education. Paris: UNESCO.

Vygotsky, L. S. (1978). Mind in Society: The Development of Higher Psychological Processes. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Wolfensberger, W. (1983). Social Role Valorization: A proposed new term for the principle of normalization. Mental Retardation, 21(6), 234–239.